One hundred years ago this week, on January 25, 1926, thirty-three Irish republican prisoners walked free from prisons across Scotland after almost four years behind bars.

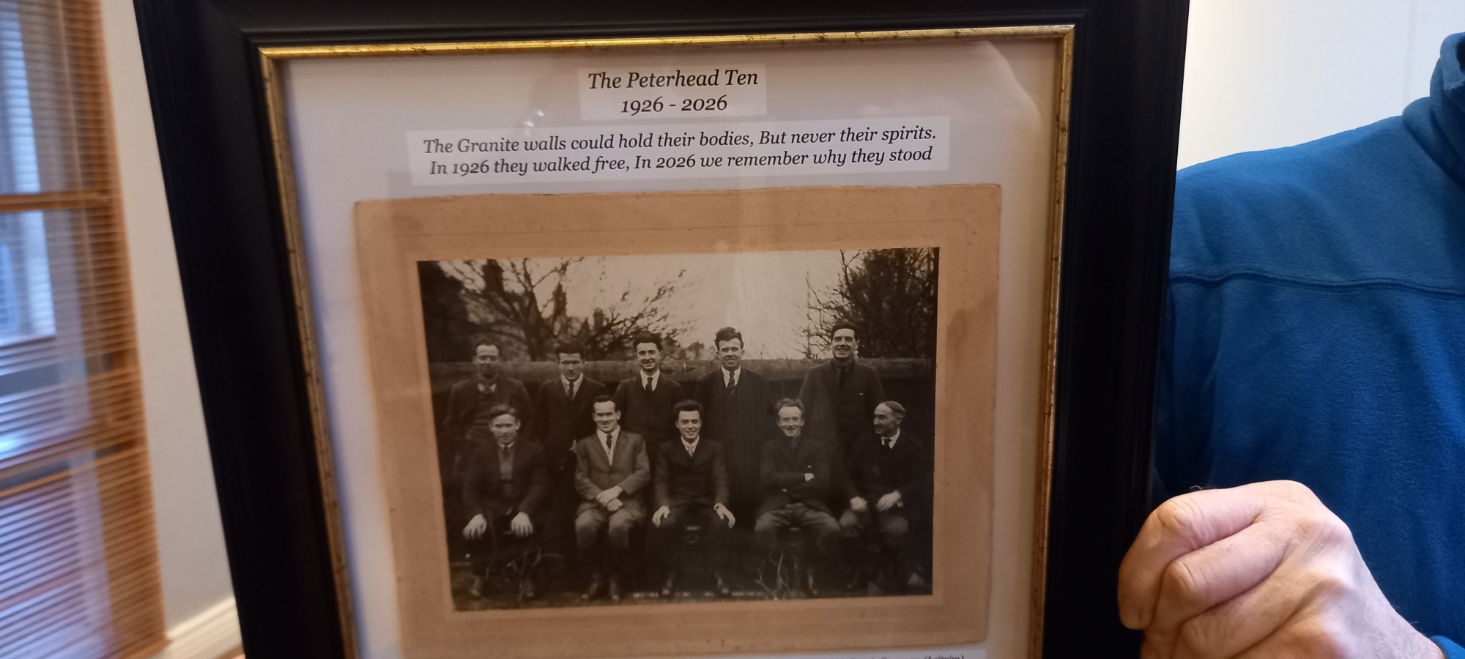

The largest group of those released came from Peterhead Prison in north-east Scotland — a brutal hard-labour convict jail — where a number of detainees had become known as the “Peterhead men”.

Their imprisonment dated back to the turbulent months following the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in December 1921, when the IRA began to split into pro- and anti-Treaty factions. In an effort to prevent division within the organisation, Michael Collins approved a secret campaign of violence against the newly established six-county state of Northern Ireland, in the hope that both sides could unite around one cause.

As part of this strategy, Collins established an IRA Ulster Northern Command, led by Frank Aiken, with Longford’s Sean MacEoin as deputy. This prompted a border campaign between January and June 1922 which involved IRA operations against Crown forces by both factions.

One of the most serious operations was a co-ordinated kidnapping raid targeting prominent unionists, organised in response to threatened executions of republican prisoners at Derry Jail. The raids took place on the night of February 7–8, 1922, involving IRA units from Longford, Leitrim and Armagh operating in Fermanagh and Tyrone.

While the operation succeeded in Tyrone — where the IRA kidnapped 21 local unionists — the Fermanagh raid ended in failure after a swift response by the RUC B Specials.

A group of IRA men, including five Leitrim republicans, were arrested outside Enniskillen. They were Bernard Sweeney (Ballinamore), John Kiernan (Newtowngore), Joe Reynolds (Kiltubrid), John Griffin, and Charlie Reynolds (Gortlettragh).

The men had been part of a thirteen-man raiding party from the IRA’s Midlands Division under the command of Commandant Sean McCurtain, a Tipperary native and friend of Sean MacEoin, who was directing the border campaign on behalf of Collins.

At their trial in Enniskillen on March 13, 1922, the defendants refused to recognise the court and argued their actions were politically motivated. Evidence was heard that the men were travelling in several cars and were found in possession of arms and explosives when stopped by police.

However, Justice Wilson rejected the argument that political motivation excused the offences, telling the court: “A crime was a crime whether it was committed by a politician, a saint or a butter merchant.” The defendants were sentenced to ten-year prison terms.

Following their convictions, the men were held in Derry Jail before being transferred to Peterhead Prison in August 1922 under a special arrangement with Scottish authorities.

By that stage, the Irish Civil War had erupted in the newly established Irish Free State, leaving almost 1,500 dead, including major figures from both sides such as Michael Collins, Harry Boland, Arthur Griffith and Liam Mellows.

Although anti-Treaty prisoners held by the Free State were gradually released after the war ended in May 1923, IRA men imprisoned in Northern Ireland — including the Peterhead prisoners — remained incarcerated in Scotland.

Peterhead Prison, opened in 1888, was Scotland’s only convict prison and was notorious for its harsh conditions. Prisoners were forced into hard labour in a nearby granite quarry, enduring overcrowded and freezing cells with minimal sanitation. Each day, inmates were marched to the quarry to break stones using seven- and fourteen-pound hammers.

Recalling the experience, Leitrim republican Berney Sweeney later said: “No one could appreciate how we were treated there. When our comrades would be taken out for a beating, as happened frequently, we would not recognise them when they would return.”

The fate of the Peterhead prisoners became a long-running issue between the Free State and Northern Ireland governments. When Sean McCurtain was elected to the Dáil in August 1923 as a pro-Treaty Cumann na Gaedhael TD for Tipperary, calls intensified for the men’s release — but with little result.

In December 1923, President of the Executive Council W.T. Cosgrave told the Dáil: “Representations had been made on several occasions regarding the release of Mr McCurtain, but so far, I regret to say, they have not met with success.”

Even after Éamon de Valera was released as the last anti-Treaty prisoner held in the Free State in 1924, the Peterhead men remained in custody.

Their freedom eventually came as part of a tripartite agreement between the British, Irish and Northern governments on December 3, 1925, following the report of the Boundary Commission. The Commission dashed nationalist hopes of a significant border adjustment, amounting to a major diplomatic defeat for the Free State government.

Northern Ireland Prime Minister James Craig deferred the prisoner question to the British authorities, who ordered the release of 33 prisoners, including the “Peterhead men”, on January 25, 1926.

Despite the years of sacrifice and harsh imprisonment, their return was met with only a muted reaction at home. While family members and officers of the Dublin Brigade of the IRA greeted the men as they arrived at Dublin’s North Wall from Glasgow, no member of government was present.

Sean McCurtain received a huge welcome upon returning to Nenagh, but no public celebrations marked the homecoming of the Leitrim prisoners or their comrades. Contemporary newspaper coverage barely acknowledged their release.

In the years following their freedom, two of the prisoners — John Kiernan of Newtowngore, Co Leitrim, and Dubliner Sean Flood — died, while Joe Reynolds of Kiltubrid and Frank Reilly of Ballinamuck emigrated to the United States in search of a new start.

A century on, their stories remain largely forgotten. As Ireland marks 100 years since their release, renewed attention is being urged for the men whose quiet suffering and sacrifice slipped through the cracks of national memory.

Padraig McGarty is the author of Leitrim: The Irish Revolution 1912–1923, published by Four Courts Press.

READ MORE: Leitrim farmers warned of potential dangers of imported animal feed

Subscribe or register today to discover more from DonegalLive.ie

Buy the e-paper of the Donegal Democrat, Donegal People's Press, Donegal Post and Inish Times here for instant access to Donegal's premier news titles.

Keep up with the latest news from Donegal with our daily newsletter featuring the most important stories of the day delivered to your inbox every evening at 5pm.