orace Plunkett, founder of the co-operative movement

The Great Famine (1845–9) and its ongoing impact was catastrophic for rural Ireland. Not only did the Famine itself have direct and devastating consequences for the population, reducing it dramatically through death and forced emigration, but such were the inequities that it laid bare – far too many very small farms and, at the same time, far too many very big farms – that the population of rural Ireland did not begin to recover for well over a century.

The western seaboard counties were effected most and none more than Leitrim. In 1841 its population was 155,297; by 1971 it was 28,360. Between the Famine and the 1970s, rural Leitrim had remained in crisis and it needed help, specifically in the context of rural development.

Fortunately, that help did become available. At the turn of the twentieth century, Horace Plunkett, founder of the co-operative movement, made it his next mission to address the necessity for development in rural Ireland more generally. He campaigned for a separate department of agriculture for Ireland within the UK and, on foot of this, for greatly enhanced support for Irish farmers.

In 1900 the Department of Agriculture and Technical Instruction opened in Dublin and, together with Ireland’s new county councils, created in 1898, started employing teams of scientific instructors who would work with farmers in every county to help them earn better livelihoods from farming.

Leitrim immediately struggled to recruit all three types of instructor: the general agricultural instructor, the horticultural instructor and the poultry-keeping and butter-making instructor. Taking the general agricultural instructor, Plunkett had envisaged that each county would have at least two but the new course that trained them, initially at the Royal College of Science (today Government Buildings) and then at UCD would not produce graduates for several years. That notwithstanding, it was 1945 before Leitrim had its basic complement of two and for a county with amongst the smallest farms in Ireland that was not auspicious. Nonetheless, while the continuing population decline might not have reflected it, the foundations for more efficient, more profitable, farming were being put down by the embryonic advisory service.

By the 1970s, the advisory service in Leitrim was more fully formed, with 10 agricultural instructors assigned to work with farmers in each parish – unlike in other counties where they were assigned entire districts – and a game of inches was pursued to eke as much as possible from every acre.

Success was generally modest but during 1970–73 the 54 Leitrim farmers working with instructors as part of the Small Farm (Incentive Bonus) Scheme saw their average income rise by 107%.

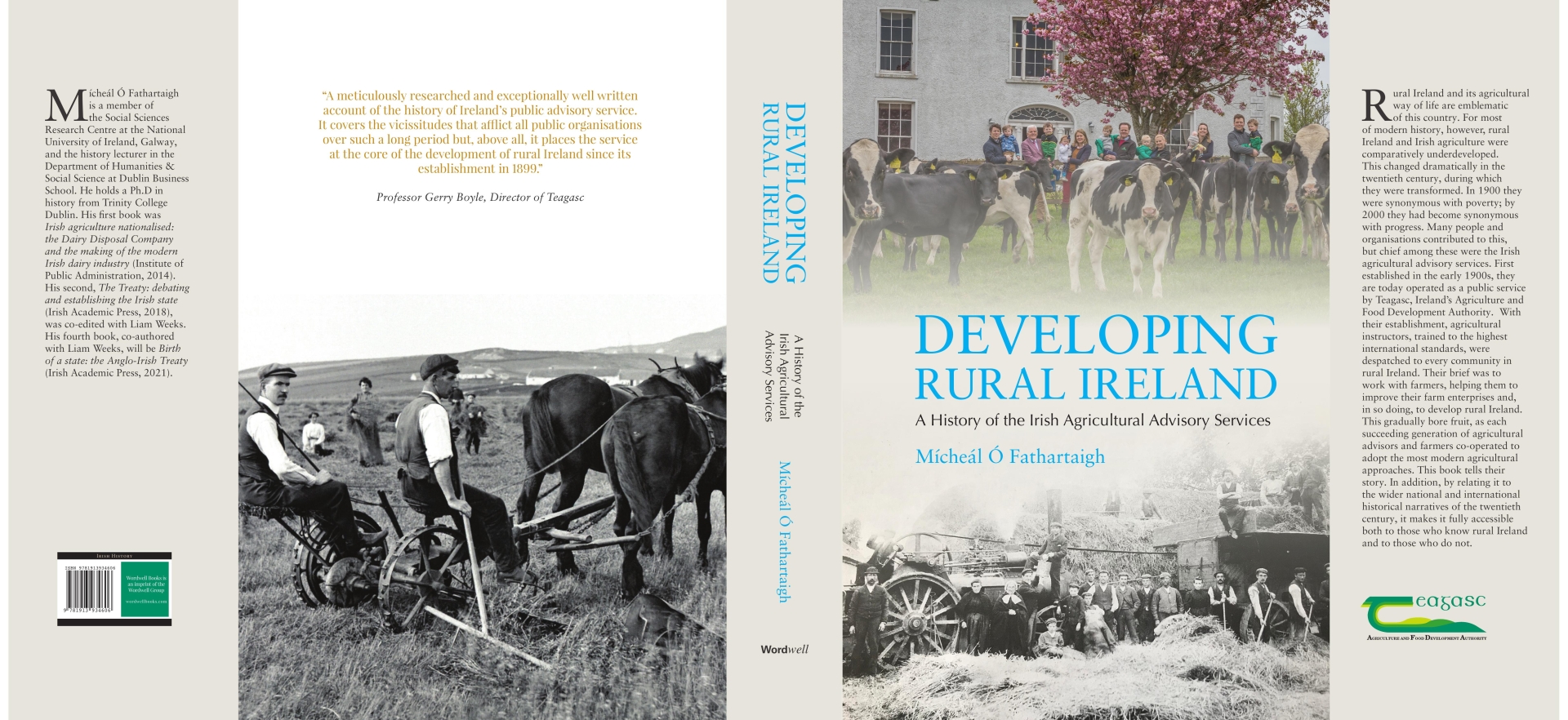

Delayed as it was in Leitrim, the legacy of the Famine was finally being challenged by farmers and advisors in partnership and a broadly upward trajectory for rural development in Leitrim was established for the rest of the twentieth century. The full extent of this story is detailed in my recent book, Developing Rural Ireland: A History of the Irish Agricultural Advisory Services.

Dr Mícheál Ó Fathartaigh is the author of Developing Rural Ireland: A History of the Irish Agricultural Advisory Services (Wordwell Books, 2021).

Subscribe or register today to discover more from DonegalLive.ie

Buy the e-paper of the Donegal Democrat, Donegal People's Press, Donegal Post and Inish Times here for instant access to Donegal's premier news titles.

Keep up with the latest news from Donegal with our daily newsletter featuring the most important stories of the day delivered to your inbox every evening at 5pm.